A fresh and newly provisioned server is a clean slate for a lot of ideas and projects. Here are the various things you can do on a new Ubuntu server to ensure smooth project setup.

Update and upgrade

Install the latest security patches and upgrades to the existing applications.

From our partners:

$ sudo apt-get update

$ sudo apt-get upgrade

Add a new sudo-er user

With a newly provisioned server you will be given a default user account. This account usually have access to root or is a sudo-er. The user you add here requires you to use an SSH key instead of password. You need to create your own keys using tools or CLI.

If you already have your key pair, you can continue to step 5

01. To generate a key-pair in your terminal, execute the following. An email address is usually provided as the comment for the key.

Format

$ ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096 -C "{{comment}}"Example

$ ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 4096 -C "[email protected]"

02. Enter the directory to save the key pair. If left empty, it will be saved in the default path at /home/{user}/.ssh/id_rsa.

03. Next is you would be asked a passphrase. A passphrase provides additional authentication for the key pair. You can ignore and press enter if you opt to.

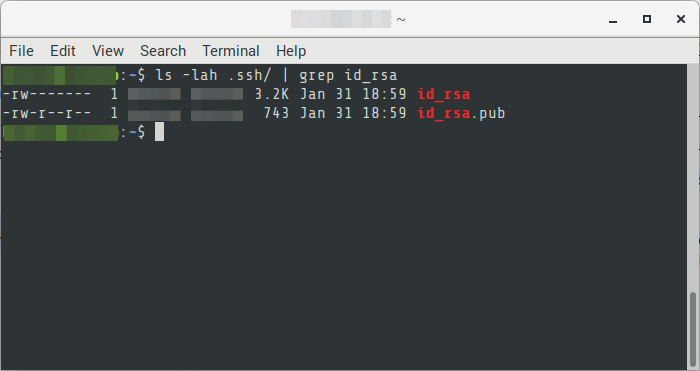

04. In the directory you specified or in the default, it will generate 2 files. A public and private key. The public key has the extension .pub while the private has no extension.

On the new ubuntu server

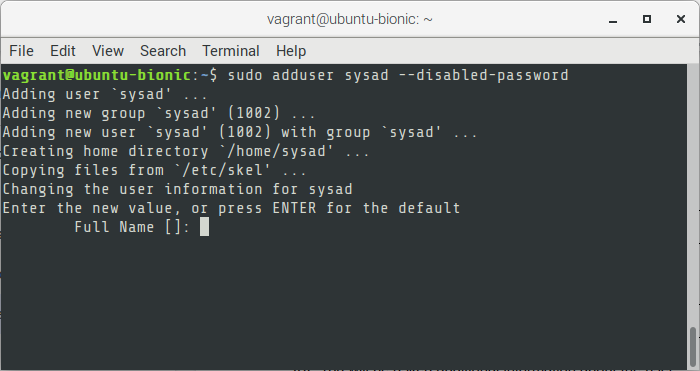

05. On your new ubuntu server, create a new user.

Format

$ sudo adduser {{username}} --disabled-passwordExample

$ sudo adduser sysad --disabled-password

06. You will be asked additional information about the user. All of these are optional

- Full Name

- Room Number

- Work Phone

- Home Phone

- Other

07. Add the new user to the sudo-er group

Format

$ sudo usermod -aG sudo {{username}}Example

$ sudo usermod -aG sudo sysad

08. Switch access to the new user

Format

$ sudo su - {{username}}Example

$ sudo su - sysad

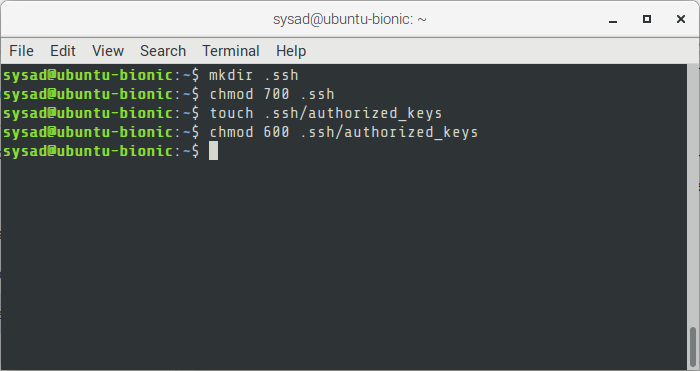

09. You will be switched to the user. Next is to create the authorized_keys file, which will contain the public key that was previously created.

$ mkdir .ssh

$ chmod 700 .ssh

$ touch .ssh/authorized_keys

$ chmod 600 .ssh/authorized_keys

10. Edit the authorized_keys file and append the content of the public key.

$ nano .ssh/authorized_keys

11. Copy the content. Then press Ctrl+O and Enter to save the changes. Then Ctrl-X and Enter to exit from the editor.

12. Exit from the user, then exit from the remote server.

$ exit

$ exit

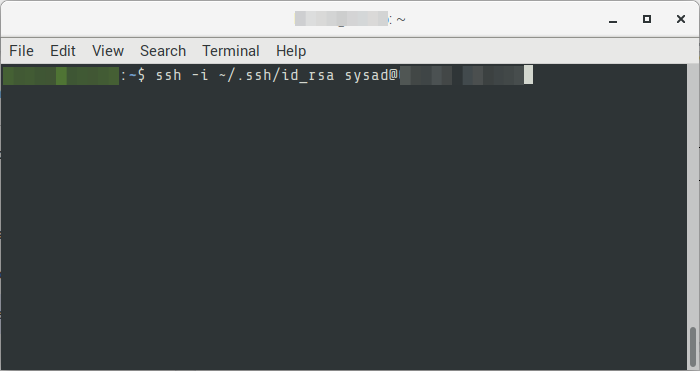

13. You should now be in your local machine. Try accessing the remote machine using the new user and private key.

Format

$ ssh -i {{rsa-key-private}} {{username}}@{{hostname-or-ip}}Example

$ ssh -i ~/.ssh/id_rsa [email protected]

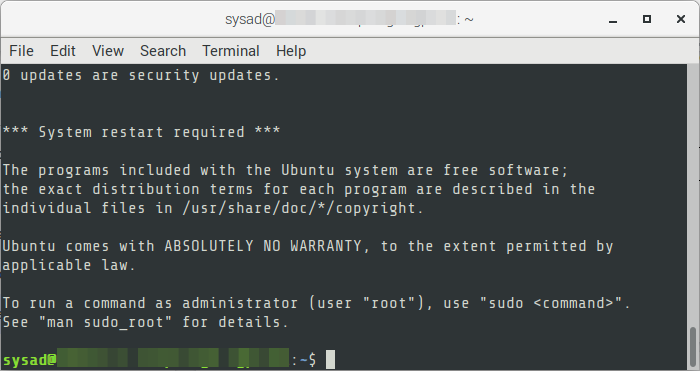

14. You should now be remotely accessing the server with the new username.

Configuring Swap

01. Define the swap directory and swap size

Format

$ sudo fallocate -l {{swap-size}} {{swap-path}}Example

$ sudo fallocate -l 1G /swapfile02. Verify the swap directory

Format

$ ls -lh {{swap-path}}Example

$ ls -lh /swapfile03. Update the permission the swap directory, setting only root to have the only access to it

Format

$ sudo chmod 600 {{swap-path}}Example

$ sudo chmod 600 /swapfile

04. Mark as swap

Format

$ sudo mkswap {{swap-path}}Example

$ sudo mkswap /swapfile

05. Enable swap

Format

$ sudo swapon {{swap-path}}Example

$ sudo swapon /swapfile06. Verify the swap configuration, it should now show the swap directory

$ sudo swapon --show07. Make the swap to be permanent and applied on boot. Backup of the fstab config also.

Format

$ sudo cp /etc/fstab /etc/fstab.bak

$ echo '{{swap-path}} none swap sw 0 0' | sudo tee -a /etc/fstabExample

$ sudo cp /etc/fstab /etc/fstab.bak

$ echo '/swapfile none swap sw 0 0' | sudo tee -a /etc/fstab

08. Update the swappiness factor if preferred. This value determines the behavior if it should put it into swap rather than RAM. The lower the value, the less chance it will put into swap. The value ranges from 0 to 100. With the default swappiness value of 60.

Set the swappiness by running the following command

Format

$ sudo sysctl vm.swappiness={{swappiness-value}}Example

$ sudo sysctl vm.swappiness=10

To make it permanent, update the /etc/sysctl.conf file.

$ sudo nano /etc/sysctl.conf

And add the following add the bottom

Format

$ vm.swappiness={{swappiness-value}}Example

$ vm.swappiness=10

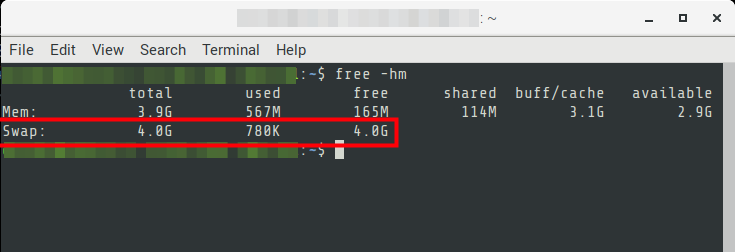

09. Verify the swap using the following command

$ free -hm

Add timestamp to your bash history

01. Switch OS user you want to add timestamp

$ sudo su - {os-user}

02. Run the following to update the bashrc file.

$ echo 'export HISTTIMEFORMAT="%y %m %d %T "' >> ~/.bashrc

03. Then apply the changes made

$ source ~/.bashrc

04. Check the bash history if it has been updated. It should now output the history with date and time info. Note that commands executed before this process is not the actual date and time. But for the new commands, it will reflect the date and time when it is executed.

$ historyFor enquiries, product placements, sponsorships, and collaborations, connect with us at [email protected]. We'd love to hear from you!

Our humans need coffee too! Your support is highly appreciated, thank you!