Let’s talk about the mistakes beginner programmers usually make but let me make one thing clear first. If you are a beginner programmer, this is not meant to make you feel bad about the mistakes that you might be making but rather to make you aware of them, teach you to spot signs of them, and remind you to avoid them.

I have made many of these mistakes in the past. It is how I learned to do better. Do not feel bad if you are making these mistakes today. Just learn why they are classified here as mistakes. I am happy to have formed coding habits to help me avoid them. You should do too.

From our partners:

The mistakes are not presented here in any particular order.

1. Writing Code Without Planning

High-quality content cannot be created easily. It requires careful thinking and research. High-quality programs are no exception.

Writing quality programs is a process with a flow:

Think. Research. Plan. Write. Validate. Modify.

Unfortunately, there is no good acronym for this. You need to create a habit to always go through the right amount of these activities.

One of the biggest mistakes beginner programmers make is to start writing code right away without much thinking and researching. While this might work for a small stand-alone application, it has a big, negative effect on larger applications.

Just like you need to think before saying anything you might regret, you need to think before you code anything you might regret. Coding is also a way to communicate your thoughts.

When angry, count to 10 before you speak. If very angry, a hundred.

— Thomas Jefferson

Jefferson’s advice applies to coding as well:

When reviewing code, count to 10 before you refactor a line. If the code does not have tests, a hundred.

— Samer Buna

Programming is mostly about reading previous code, researching what is needed and how it fits with the current system, and planning the writing of features with small, testable increments. The actual writing of lines of code is probably only 10% of the whole process.

Do not think about programming as writing lines of code. Programming is a logic-based creativity that needs nurturing.

2. Planning Too Much Before Writing Code

Yes. Planning before jumping into code is a good thing, but even good things can hurt you when you do too much of them. Too much healthy water might poison you.

Do not look for a perfect plan. That does not exist in the world of programming. Look for a good-enough plan, something that you can use to get started. The truth is, your plan will change, but what it was good for is to force you into some structure that leads to more clarity in your code. Too much planning is simply a waste of your time.

I am only talking about planning small features. Planning all the features at once should simply be outlawed! It is what we call the Waterfall Approach, which is a system linear plan with distinct steps that are to be finished one by one. You can imagine how much planning that approach needs. This is not the kind of planning I am talking about here. The waterfall approach does not work. Anything complicated can only be implemented with agile adaptations to reality.

Writing programs has to be a responsive activity. You will add features you would never have thought of in a waterfall plan. You will remove features because of reasons you would never have considered in a waterfall plan. You need to fix bugs and adapt to changes. You need to be agile.

However, always plan your next few features. Do that very carefully because too little planning and too much planning can both hurt the quality of your code. The quality of your code is not something you can risk.

3. Underestimating the Importance of Code Quality

If you can only focus on one aspect of the code that you write, it should be its readability. Unclear code is trash. It is not even recyclable.

Never underestimate the importance of code quality. Look at coding as a way to communicate implementations. Your main job as a coder is to clearly communicate the implementations of any solutions that you are working on.

One of my favorite quotes about programming is:

Always code as if the guy who ends up maintaining your code will be a violent psychopath who knows where you live.

— John Woods

Brilliant advice, John!

Even the small things matter. For example, if you are not consistent with your indentation and capitalization, you should simply lose your license to code.

tHIS is

WAY MORE important

than

you think

Another simple thing is the use of long lines. Anything beyond 80 characters is much harder to read. You might be tempted to place some long condition on the same line to keep an if-statement block more visible. Do not do that. Just never go beyond the 80 character limit, ever.

Many of the simple problems like these can be easily fixed with linting and formatting tools. In JavaScript, we have two excellent tools that work perfectly together: ESLint and Prettier. Do yourself a favor and always use them.

Here are a few more mistakes related to code quality:

- Using many lines in a function or a file. You should always break long code into smaller chunks that can be tested and managed separately.

Any function that has more than 10 lines is just too long.

- Using double negatives. Please do not not not do that.

Using double negatives is just very not not wrong.

- Using short, generic, or type-based variable names. Give your variables descriptive and non-ambiguous names.

There are only two hard things in Computer Science: cache invalidation and naming things.

— Phil Karlton

- Hard-coding primitive strings and numbers without descriptions. If you want to write logic that depends on a primitive string or number, put that value in a constant and give it a good name.

const answerToLifeTheUniverseAndEverething = 42;

- Using sloppy shortcuts and workarounds to avoid spending more time around simple problems. Do not dance around problems. Face your realities.

- Thinking that longer code is better. Shorter code is better in most cases. Only write longer versions if they make the code more readable. For example, do not use clever one-liners and nested ternary expressions just to keep the code shorter, but also do not intentionally make the code longer when it does not need to be. Deleting unnecessary code is the best thing you can do in any program.

Measuring programming progress by lines of code is like measuring aircraft building progress by weight.

— Bill Gates

- The excessive use of conditional logic. Most of what you think needs conditional logic can be accomplished without it. Consider all the alternatives and pick exclusively based on readability. Do not optimize for performance unless you can measure. Related: avoid yoda conditions and assignments within conditionals.

4. Picking the First Solution

This is a subtle sign of a true newbie. They get presented with a problem, they find a solution, and just run with it. They rush the implementation right away before thinking about the complexities and potential failures of the identified solution.

While the first solution might be tempting, the good solutions are usually discovered once you start questioning all the solutions that you find. If you cannot think of multiple solutions to a problem, that is probably a sign that you do not completely understand the problem.

Your job as a professional programmer is not to find a solution to the problem. It is to find the simplest solution to the problem. By “simple” I mean the solution has to work correctly and perform adequately but still be simple enough to read, understand, and maintain.

There are two ways of constructing a software design. One way is to make it so simple that there are obviously no deficiencies, and the other way is to make it so complicated that there are no obvious deficiencies.

— C.A.R. Hoare

5. Not Quitting

Another mistake newbies make is sticking with the first solution even after they identify that it might not be the best approach. This is probably psychologically related to the “not-quitting” mentality. This is a good mentality to have in most activities, but it should not apply to programming. In fact, when it comes to writing programs, the right mentality is fail early and fail often.

The minute you begin doubting a solution, you should consider throwing it away and re-thinking the problem. This is true no matter how much you were invested in that solution. Source control tools like GIT can help you branch off and experiment with many different solutions. Leverage that. Do not be attached to code because of how much effort you put into it. Bad code needs to be discarded.

6. Not Googling

There has been many instances where I wasted precious time trying to solve a problem when I should have just researched it.

Unless you are using a bleeding-edge technology, when you run into a problem, chances are someone else ran into the same problem and found a solution for it. Save yourself some time and Google It First.

Sometimes, Googling will reveal that what you think is a problem is really not, and what you need to do is not fix it but rather embrace it. Do not assume that you know everything needed to pick a solution to a problem. Google will surprise you.

However, another sign of a newbie is copying and using code as is without understanding it. While that code might correctly solve your problem, you should never use any line of code that you do not fully understand. If you want to be a creative coder, never think that you know what you’re doing.

The most dangerous thought that you can have as a creative person is to think that you know what you’re doing.

— Bret Victor

7. Not Using Encapsulation

This point is not about using the object-oriented paradigm. The use of the encapsulation concept is always useful. Not using encapsulation often leads to harder-to-maintain systems.

A feature should have only one place in the code that handles it. That is usually the responsibility of a single object. That object should only reveal what is absolutely necessary for other objects of the application to use it. This is not about secrecy but rather about the concept of reducing dependencies between different parts of an application. Sticking with these rules allows you to safely make changes in the internals of your classes, objects, and functions without worrying about breaking things in a bigger scale.

Conceptual units of logic and state should get their own classes. By class, I mean a blueprint template. This can be an actual Class object or a Function object. You might also identify it as a Module or a Package.

Within a class of logic, self-contained pieces of tasks should get their own methods. Methods should do one thing and do that thing well. Similar classes should use the same method names.

Newbies usually do not have the instinct to start a new class for a conceptual unit and they cannot identify what can be self-contained. If you see a Util class that has been used as a dumping ground for many things that do not belong together, that is a sign of newbie code. If you make a simple change and then discover that the change has a cascading effect and you need to do many changes elsewhere, that is another sign of newbie code.

Before adding a method to a class or adding more responsibilities to a method, think and question your instincts. You need time here. Do not skip or think that you will refactor that later. Just do it right the first time.

The big idea here is that you want your code to have High Cohesion and Low Coupling, which is just a fancy term that means keep related code together (in a class) and reduce the dependencies between different classes.

8. Planning for the Unknown

It is often tempting to think beyond the solution that you are writing. All sort of what-ifs will pop into your head with every line of code that you write. This is a good thing for testing edge cases, but it just wrong to use as a driver for potential needs.

You need to identify which of these two main categories your what-ifs belong to. Do not write code that you do not need today. Do not plan for the unknown future.

Writing a feature because you think that you might need it in the future is simply wrong. Do not do it.

Always write the minimum amount of code that you need today for the solution that you are implementing. Handle edge-cases, sure, but do not add edge-features.

Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell.

— Edward Abbey

9. Not Using the Right Data Structures

When preparing for interviews, beginner programmers usually put too much focus on algorithms. It is good to identify good algorithms and use them when needed, but memorizing them will probably never attribute to your programming genius.

However, memorizing the strengths and weaknesses of the various data structures that you can use in your language will make you a better developer.

Using the wrong data structure is a big and strongly-lit billboard sign that screams newbie code here.

This is not a book to teach you about data structures but let me mention a couple of quick examples:

Example: Using lists (arrays) instead of maps (objects)

The most common data structure mistake is probably the use of lists instead of maps to manage a list of records. Yes, to manage a LIST of records you should use a MAP.

In JavaScript, for example, the most common list structure is an array and the most common map structure is an object (there is also a map structure in modern JavaScript).

Using lists over maps is often wrong. While this point is really only true for large collections, I would say just stick with it all the time. There are few specific cases where lists might be a better option than maps and these cases are vanishing in modern languages. Just use maps.

The main reason this is important is because accessing elements in maps is a lot faster than accessing elements in lists. Accessing elements is something that you will be doing often.

Lists used to be important because they guarantee the order of elements. However, modern map structures can do that too.

Example: Not Using Stacks

When writing any code that requires some form of recursion, it is a lot easier to just use the concept of recursion. However, it is usually hard to optimize recursive code, especially in single-threaded environments.

Optimizing recursive code also depends on what recursive functions return. For example, optimizing a recursive function that returns two or more calls to itself is a lot harder than optimizing a recursive function that simply returns a single call to itself.

What beginners often forget is that there is an alternative to recursion. You can just use a Stack structure. Push function calls to a Stack yourself and start popping them out when you are ready to traverse the calls back.

10. Making Existing Code Worse Than What They Started With

Imagine that you were given a messy room like this:

You were then asked to add an item to that room. Since it is a big mess already, you might be tempted to put that item anywhere. You can be done with your task in a few seconds.

Do not do that with messy code. Do not make it worse! Always leave the code a bit cleaner that when you started to work with it.

The right thing to do to the room above is to clean what is needed in order to place the new item in the right place. For example, if the item is a piece of clothing that needs to be placed in a closet, you need to clear a path to that closet. That is part of doing your task correctly.

Here are a few wrong practices that usually make the code a bigger mess than what it was (not a complete list):

- Duplicating code. If you copy/paste a code section to only change a line after that, you are simply duplicating code and making a bigger mess. This is like introducing another chair with a lower base in that messy room instead of investing in a new chair that is height-adjustable. Always keep the concept of abstraction in your mind and use it when you can.

- Not using configuration files. If you need to use a value that could potentially be different on different environments or at different times, that value belongs in a configuration file. If you need to use a value in multiple places in your code, that value belongs in a configuration file. Just ask yourself this question all the time when you introduce a new value to the code: does this value belong in a configuration file? The answer will most likely be yes.

- Using unnecessary conditional statements and temporary variables. Every if-statement is a logic branch that needs to be at-least double tested. When you can avoid conditionals without sacrificing readability, you should. The major problem with this is extending a function with a branch logic instead of introducing another function. Every time you think you need an if-statement or a new function variable you should ask yourself: am I changing code in the right level or should I go a higher level?

On the topic of unnecessary if-statements, think about this code:

function isOdd(number) {

if (number % 2 === 1) {

return true;

} else {

return false;

}

}

The isOdd function above has a few problems but can you see the most obvious one?

It uses an unnecessary if-statement. Here is an equivalent code:

function isOdd(number) {

return (number % 2 === 1);

};

11. Writing Comments About the Obvious Things

I avoid writing comments when I can. I think most comments can be replaced with better named elements in your code.

For example, instead of the following code:

// This function sums only odd numbers in an array

const sum = (val) => {

return val.reduce((a, b) => {

if (b % 2 === 1) { // if the current number is odd

a+=b; // Add current number to accumulator

}

return a; // The accumulator

}, 0);

};

The same code can be written without comments like this:

const sumOddValues = (array) => {

return array.reduce((accumulator, currentNumber) => {

if (isOdd(currentNumber)) {

return accumulator + currentNumber;

}

return accumulator;

}, 0);

};

Just using better names for functions and arguments simply makes most comments unnecessary. Keep that in mind before writing any comment.

However, sometimes you are forced into situations where the only clarity you can add to the code is via comments. This is when you should structure your comments to answer the question of WHY this code rather that the question of WHAT is this code doing.

If you are strongly tempted to write a WHAT comment to clarify the code, please do not point out the obvious. Here is an example of some newbie comments:

// create a variable and initialize it to 0

let sum = 0;

// Loop over array

array.forEach(

// For each number in the array

(number) => {

// Add the current number to the sum variable

sum += number;

}

);

Do not be that programmer. Do not accept that code. Remove these comments if you have to deal with them. If you happen to be employing programmers who write comments like the above, go fire them, right now.

12. Not Writing Tests

I am going to keep this point simple. If you think you are an expert programmer and that thinking gives you the confidence to write code without tests, you are a newbie in my book (literally).

If you are not writing tests in code, you are most likely testing your program some other way, manually. If you are building a web application, you will be refreshing and interacting with the application after every few lines of code.

I do that too. There is nothing wrong about manually testing your code. However, you should manually test your code to figure out how to automatically test it. If you successfully test an interaction with your application, you should go back to your code editor and write code to automatically perform the exact same interaction the next time you add more code to the project.

You are a human being. You are going to forget to test all previously successful validations after each code change. Make the computer do that for you!

If you can, start by guessing or designing your validations even before you write the code to satisfy them. Testing-driven development (TDD) is not just some fancy hype. It positively affects the way you think about your features and how to come up with a better design for them.

TDD is not for everyone and it does not work well for every project, but if you can utilize it (even in part) you should totally do so.

13. Assuming That If Things are Working then Things are Right

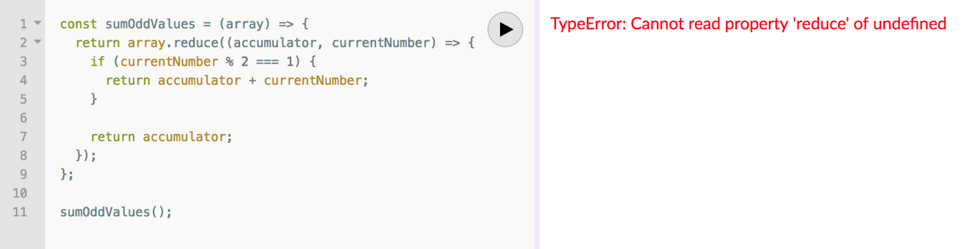

Take a look at this function that implements the sumOddValues feature. Is there anything wrong with it?

const sumOddValues = (array) => {

return array.reduce((accumulator, currentNumber) => {

if (currentNumber % 2 === 1) {

return accumulator + currentNumber;

}

return accumulator;

});

};

console.assert(

sumOddValues([1, 3, 5]) === 9

);

The assertion passes. Life is good. Right, RIGHT?

The problem with the code above is that it not complete. It correctly handles a few cases and the assertion used happens to be one of these cases.

The function above has many problems beyond that. Let me go through a few of them:

Problem #1: There is no handling for empty input. What should happen when the function is called without any arguments? Right now you get an error revealing the function’s implementation when that happens:

TypeError: Cannot read property 'reduce' of undefined.

That is usually a sign of bad code for two main reasons:

- Users of your function should not encounter implementation details about it.

- The error is not helpful for the user. Your function just did not work for them. However, if the error was more clear about the usage problem, they would know that they used the function incorrectly. For example, you can opt to have the function throw a user-defined exception like this:

TypeError: Cannot execute function for empty list.

Maybe instead of throwing an error, you need to design your function to just ignore empty input and return a sum of 0 for that. Regardless, something has to be done for this case.

Problem #2: There is no handling of invalid input. What should happen if the function is called with a string, an integer, or an object value instead of an array?

Here is what the function would throw now:

sumOddValsue(42); TypeError: array.reduce is not a function

Well, that is unfortunate because array.reduce is definitely a function!

Since we named the argument array, anything you call the function with (42 in the example above) is labeled as array within the function. The error is basically saying that 42.reduce is not a function.

You see how that error is confusing, right? Similar to Problem #1, this is happening because we do not handle this specific case.

Maybe a more helpful error would have been: 42 is not an array, dude.

Problems #1 and #2 are sometimes referred to as edge-cases. Those are some common edge-cases to plan for, but there are usually less obvious edge-cases that you need to think about as well.

Problem #3: No testing for edge-cases. Aside from the obvious ones, the function above does not handle many other edge-cases very well. For example, what happens if we use negative numbers?

sumOddValues([1, 3, 5, -13]) // => still 9

Well, -13 is an odd number. Is this the behavior that you want this function to have? Should it throw an error? Should it include the negative numbers in the sum? Or should it simply just ignore negative numbers like it is doing now? Maybe it should have been named sumPositiveOddNumbers.

You need to make a decision on this case. If you do not have a test case to document your decision, maybe leave a short comment about it in code, a why-is-this-function-doing-the-unexpected-here type of comment.

Problem #4: Not all valid cases are tested. Forget edge-cases, this function has a legitimate and very simple case that it does not handle correctly:

sumOddValues([2, 1, 3, 5]) // => 11

The 2 above was included in sum when it should not have been.

If this surprises you, try to figure out why this problem is happening in the code above.

The solution is simple, reduce accepts a second argument to be used as the initial value for the accumulator. If that argument is not provided (like in the code above), reduce will just use the first value in the collection as the initial value for the accumulator. This is why the first even value in the test above was included in the sum.

While you might have spotted this problem right away or when the code was written, this test case that revealed it should have been included in the tests, in the first place, along with many other test cases, like all-even numbers, a list that has 0 in it, and an empty list.

If you see minimal tests that do not handle many cases or ignore edge-cases, that is another sign of newbie code.

14. Not Questioning Existing Code

Unless you are a super coder who always works solo, there is no doubt that you will encounter some kind of stupid code in your life. Beginners will not recognize it and they usually assume that it is good code since it seems to be working and it has been part of the code base for a long time.

What is worse is that if the bad code uses bad practices, the beginner might be tempted to repeat that bad practice elsewhere in the code base because they learned it from what they thought was good code.

Some code looks bad but it might have a special condition around it that forced the developer to write it that way. This is a good place for a detailed comment that teaches beginners about that condition and why the code is written that way.

As a beginner, you should just assume that any code that you do not understand is a candidate for being bad. Question it. Ask about it. git blame it!

If the author of that code is long gone or cannot remember it, research that code and try to understand everything about it.

Only when you completely understand the code you get to form an opinion whether it is bad or good. Do not assume anything before that.

15. Obsessing About Best Practices

The term “best practices” is actually harmful. It implies that no further research is needed. Here is the BEST practice ever. Do not question it! There are no best practices. There are probably good practices today and for this programming language.

Some of what we previously identified as best practices in programming are labeled today as bad practices.

You can always find better practices if you invest enough time. Stop worrying about best practices and focus on what you can do best. The only valid best practices in coding are the generic ones. For example, write the highest quality code than you possibly can.

Do not do something because of a quote you read somewhere or because you saw someone else do it, or because someone said this is a best practice!

16. Obsessing About Performance

Premature optimization is the root of all evil (or at least most of it) in programming

— Donald Knuth (1974)

While programming has significantly changed since Donald Knuth wrote the above statement, I think it still holds valuable advice today.

The good rule to remember about this is: if you cannot measure the suspected efficiently problem with the code, do not attempt to optimize it.

If you are optimizing even before writing the code, chances are you are doing it prematurely.

Of course there are some obvious optimizations that you should always consider before introducing new code. For example, in Node.js, it is extremely important that you do not flood the event loop or block the call stack. This an example of an early optimization that you should always keep in mind. Ask yourself: Will the code I am thinking about block the call stack?

However, there is a more evil type of optimization that newbies usually do: Unnecessary Optimization.

Any non-obvious optimization that is carried out on any existing code without measurements is considered harmful and should be avoided. What you think is a performance gain might turn out to be a source of new, unexpected bugs.

Do not waste your time optimizing unmeasured performance problems.

17. Not Targeting the End-user Experience

What is the easiest way to add a feature to an application? Look at it from the point of view of yourself, or how it fits in the current User Interface. If the feature is to capture some kind of input from the user, append it to that form that you already have. If that feature is to add a link to a page, add it to that nested menu of links that you already have.

Do not be that developer. Be one of the professional developers who put themselves in their end-users’ shoes. They imagine what the end-users of this particular feature need and how they might behave. They think about the ways to make the feature easy for the end-users to find and use, not about the easy way to make the feature exist in the application somehow without any thoughts about that feature’s discoverability and usability.

18. Not Picking the Right Tool for the Job

Everyone has their list of favorite tools to assist them in their programming-related activates. Some tools are great and some are just bad but most tools are great for one particular thing and not so great for many others.

A hammer is a great tool to drive a nail into a wall but it is the worst tool to use with a screw. Do not use a hammer on a screw just because you “love” that hammer. Do not use a hammer on a screw just because that is the most popular hammer on amazon with 5.0 user reviews.

Relying on a tool’s popularity rather than how much it fits the problem is a sign of a true newbie.

One problem about this point is that you will probably not know the “better” tools for a certain job. Within your current knowledge, a tool might be the best tool that you know of. However, when compared to other options, it would not make the top list. You need to familiarize yourself with the tools available to you and keep an open-mind about the new tools that you can start using.

Some coders refuse to use new tools. They are comfortable with their existing tools and they probably do not want to learn any new ones. I understand that and I can relate to it, but it is simply wrong.

You can build a house with primitive tools and take your sweet time or you can invest some time and money in new super-tools and build a better house much faster. Tools are continually improving and you need to get comfortable learning about them and using them.

19. Not Understanding that Code Problems Will Cause Data Problems

An important aspect of a program is often the management of some form of data. The program will be the interface to add new records, delete old ones, and modify others.

Even the smallest bugs in a program’s code will result in an unpredictable state for the data it manages. This is especially true if all validations on the data are done entirely through the same buggy program.

Beginners might immediately connect the dots when it comes to code-data relationship. They might feel okay continuing to use some buggy code in production because feature X that is not working is not super important. The problem is that buggy code might be continually introducing data integrity problems that are not obvious at first.

What is worse is that shipping code that fixed the bugs without fixing the subtle data problems that were caused by these bugs will just accumulate more data problems that takes the case into the “unrecoverable-level” label.

How do you protect yourself from problems like these? You can simply use multiple layers of data integrity validations. Do not rely on the single user interface. Create validations on front-ends, back-ends, network communications, and databases. If that is not an option, then you have to at-least use database-level constraints.

Familiarize yourself with database constraints and use all of them when you add columns and tables to your database:

- A NOT NULL constraint on a column means that null values will be rejected for that column. If your application assumes the existence of a value for that field, its source should be defined as not null in your database.

- A UNIQUE constraint on a column means that the column cannot have duplicate values across the whole table. For example, this is great for a username or email field on a Users table.

- A CHECK constraint is a custom expression that has to evaluate to true for the data to be accepted. For example, if you have a normal percentage column whose values have to be between 0 and 100, you can use a check constraint to enforce that.

- A PRIMARY KEY constraint means that the column’s values are both not-null and unique as well. You are probably using this one. Each table in the database should have a primary key to identify its records.

- A FOREIGN KEY constraint means that the column’s values have to match values in another table column, which is usually a primary key.

Another newbie problem that is related to data integrity is the lack of thinking in terms of transactions. If multiple operations need to change the same data source and they depend on each other, they HAVE to be wrapped in a transaction that can be rolled back when one of these operations fail.

20. Reinventing the Wheel

This is a tricky point. In programming, some wheels are simply worth reinventing. Programming is not a well-defined domain. So many things change so fast and new requirements are introduced faster than any team can handle.

For example, if you need a wheel that spins at different speeds based on the time of the day, instead of customizing the wheel we all know and love, maybe we need to rethink it.

However, unless you actually need a wheel that is not used in its typical design, do not reinvent it. Just use the damn wheel.

Do not spend your precious time researching which is the best wheel out there. Just do a quick research and use what you find. Only replace wheels when you can clearly see that they do not perform as advertised.

The cool thing about programming is that most wheels are free and open for you to see their internal design. You can easily judge coding wheels by their internal design quality.

Use open-source wheels if you can! Open-source packages can be debugged and fixed easily. They can also be replaced easily. In addition, it is easier to support them in-house.

However, if you need a wheel, do not buy a whole new car and put the car that you are maintaining on top of that new car. Do not include a whole library just to use a function or two out of it.

The best example about this is the lodash library in JavaScript. If you just need to shuffle an array, just import the shuffle method. Do not import the whole freaking lodash.

21. Having the Wrong Attitude Towards Code Reviews

One sign of coding newbies is that they often look at code reviews as criticism. They do not like them. They do not appreciate them. They even fear them.

This is just wrong. If you feel that way, you need to change this attitude right away. Look at every code review as a learning opportunity. Welcome them and appreciate them. Learn from them. And most importantly, thank your reviewers when they teach you something.

You are a forever code learner. You need to accept that. Most code reviews will teach you something you did not know. Categorize them as a learning resource.

Sometimes, the reviewer will be wrong and it will be your turn to teach them something. However, if that something was not obvious from just your code, then maybe your code needs to be modified in that case. And if you need to teach your reviewer something anyway, just know that teaching is one of the most rewarding activities that you can do as a programmer. Look at me! I dedicated more than half of my working time to teaching. Do you think I do that just for the money?

22. Not Using Source Control

Newbies sometimes underestimate the power of a good source/revision control system, and by good I mean Git.

Source control is not about just pushing your changes for others to have and build on. It is a lot bigger than that.

Source control is about clear history. Code will be questioned and the history of the progress of that code will help answer some of the tough questions. This is why we care about commit messages. They are yet another channel to communicate your implementations and using them with small commits help future maintainers of your code figure out how the code reached the state that it is in right now.

Commit often and commit early and for the love of consistency use present tense verbs in your commit subject line. Be detailed with your messages but keep in mind that they should be summaries. If you need more than a few lines in them, that is probably a sign that your commit is simply too long. Rebase!

Do not include anything unnecessary in your commit messages. For example, do not list the files that were added, modified, or deleted in your commit summaries. That list exists in the commit object itself and can be easily displayed with some Git command arguments. It would simply be noise in the summary message. Some teams like to have different summaries per file changed and I see that as another sign of a commit that is too big.

Source control is also about discoverability. If you encounter a function and you start questioning its need or design, you can find the commit that introduced it and see the context of that function. Commits can even help you identify what code introduced a bug into the program. Git even offers a binary search within commits to locate the single guilty commit that introduced a bug.

Source control can also be leveraged in wonderful ways even before the changes become official commits. The use of features like staging changes, patching selectively, resetting, stashing, amending, applying, diffing, reversing and many others add some rich tools to your coding flow. Understand them, learn them, use them, and appreciate them.

The less Git features you know, the more of a newbie you are in my book.

This, again, will not be a point about functional programming versus other paradigms. That is a topic for another book.

This is just about the fact that shared state is a source of problems and should be avoided, if possible. If that is not possible, the use of shared state should be kept to an absolute minimum.

What beginner programmers might not realize is that every variable you define represents a shared state. It holds data that can be changed by all elements in the same scope as that variable. The more global the scope is, the worse the span of this shared state. Try to keep new states contained in small scopes and make sure they do not leak upward.

The big problem with shared state starts to happen when multiple resources need to change that state together in the same tick of the event loop (in event-loop-based environments). Race conditions will happen.

Here is the thing: a newbie might be tempted to use a timer as a workaround for this shared state race condition problem, especially if they have to deal with a data lock issue. That is a big red flag. Do not do it. Watch for it, point it out in code reviews, and never accept it.

24. Having the Wrong Attitude About Errors

Errors are a good thing. They mean you are making progress. They mean you have an easy follow-up change to make more progress.

Expert programmers love errors. Newbies hate them.

If seeing these wonderful little red error messages bother you, you need to change that attitude. You need to look at them as helpers. You need to deal with them. You need to leverage them to make progress.

Some errors need to be upgraded to exceptions. Exceptions are user-defined errors that you need to plan for. Some errors need to be left alone. They need to crash the application and make it exit.

25. Not Taking Breaks

You are a human and your brain needs breaks. Your body also needs breaks. You will often be in the zone and forget to take breaks. I look at that as another sign of newbies. This is not something you can compromise. Integrate something in your workflow that forces you to take breaks. Take a lot of short breaks. Leave your chair and take a short walk and use it to think about what you need to do next. Come back to the code with fresh eyes.

This has been a long read. You deserve a break.

This feature is originally appeared in jscomplete.com

For enquiries, product placements, sponsorships, and collaborations, connect with us at [email protected]. We'd love to hear from you!

Our humans need coffee too! Your support is highly appreciated, thank you!